At the 2018 MET gala, Kim Kardashian posed for a photograph with a gold sarcophagus on display because it matched her gold metallic dress. Coincidentally, that same photograph helped solve one of the most mysterious and unsolved cases of looted artifacts from Egypt during the 2011 uprisings. When I first learned that a Kardashian ‘cracked the case’ I giggled a little bit.

On the one hand, I find this incident fitting for the times in which popular culture aided the restitution of an otherwise unsolved and discarded case. On the other hand, I find it terrifying that all it took was one picture to shed light on a stolen artifact in the MET––and a rather large, loud, and opulent display––and cannot help but think of the many other looted artifacts currently on public display there, or perhaps hidden away in storage.

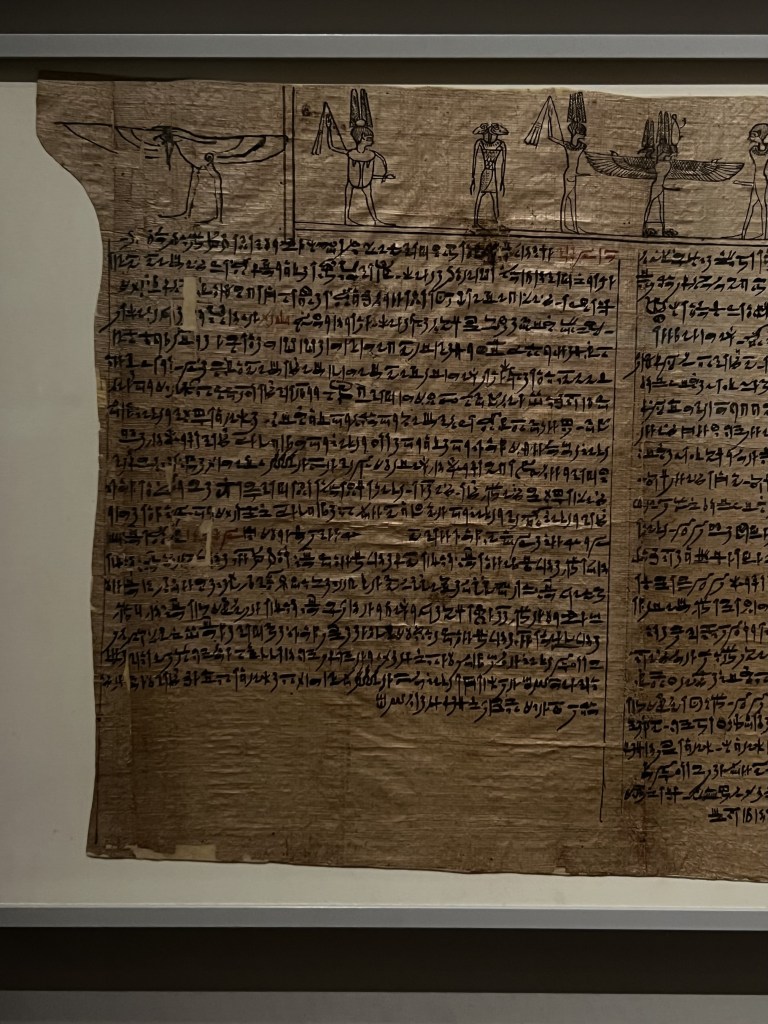

How are we to know now the extent of our dispossession, which artifacts are looted and which are not? If you walk into the MET, as I did in early 2021 and again this summer, you would find that half of the first floor is dedicated to Ancient Egyptian art and artifacts. How are we to trace the provenance for each piece when they exist tenfold in the Crime Palace? The term ‘Crime Palace’, coined by Michael Rakowitz, refers to Western museums that house often looted non-Western heritage.

Often times, as was the case with the now restituted sarcophagus of Nedjem Ankh, the provenance of these artifacts is difficult to place and notoriously hazy to trace given forgery, fabrication, and reproduction across time and space, through their migration from one country to another. My grievances with these artifacts is not that they are only looted (though of course, this is obvious) but the matter of fact that they exist in and are rendered the property of a Crime Palace such as the MET.

The other day, my mother told me about an article she read. It said that if we gathered all the Ancient Egyptian artifacts from Western museums, we’d have enough to reveal the entire history of Ancient Egypt, like a treasure trove. Smuggling and looting aside, while I understand the notion of gift giving and the exchange of relics and artifacts as a trade for political and economical benefits, I am of the belief and philosophy that my country’s relics and heritage should not be put on display far away from home, be controlled, and have their contexts obscured and rendered void of their origin.

I have a very strong and cemented opinion on where artifacts should be placed and who gets to show them for institutional or national gain. But, instead of listing these reasons one by one, I’d rather recollect my experience of walking through the Ancient Egyptian wing at the MET this summer as to better enunciate my firm opinion on the display of and acquisition of mainly objects and relics from the South West Asian and North African regions in Western museums.

On the 25th of July, 2023 I visited the MET Museum in New York City. Upon arriving, I immediately bolted toward the Ancient Egyptian wing––not because I hadn’t seen it before or because I am Egyptian––but because of my prerogative as an artist to sit with the artifacts and antiquities and to begin understanding their points of view. In other words, I wanted to experience the movement and saturation of the museum from their perspectives. I began my walk from the entrance to the Ancient Egyptian wing and continued on, and on, and on. The Ancient Egyptian wing did not end, it separated into larger halls and even larger domes stretching out onto the outside of the museum halls into their own makeshift Crime Palaces––it was unfurling, unending, uninterrupted, and unsettling.

Along my walk throughout the Ancient Egyptian wing, I could not help but eavesdrop on rather casual yet violently reductive conversations from what I assume is a largely North American demographic. Apparently, the Ancient Egyptians, because of multiple drawings that depict groups of people, always traveled in groups and jumped off ships, according to one North American woman who quickly became an expert on Ancient Egyptian studies after standing in front of a drawing for thirty seconds. Another fun fact I never knew about the Ancient Egyptians is that apparently, hieroglyphics derives from Hebrew script! While I am no scholar of linguistics or history, I can confidently write that fun fact off as false and historically inaccurate, given that Ancient Egypt had existed and was existing long before any monotheistic religion. However, because these adlibs had sparked my curiosity even more, I decided to piggyback off and join a guided tour that was taking place adjacent to me.

The tour guide spoke of black magic, aliens, and of the entire legacy of pharaohs and dynasties that had ruled Ancient Egypt being racially black to a swarm of Caucasian heads nodding and laughing. Despite my best efforts to maintain my composure and to take in what I was hearing from one ear and out the other, my body jolted and I spoke out:

hi, excuse me, sorry but I don’t think that’s true. I think a classic example of this is Queen Cleopatra who was not even Egyptian but Macedonian-Greek and ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. Also, aliens did not build the pyramids. I find it both frustrating and amusing that anything remotely spectacular or monumental can never be ascribed to black or brown people while simultaneously, you all bask in the magic and opulence of Ancient Egypt only to further otherize us, making it seem and feel like this was a breadth of history that is separate from yours, when in reality is a breadth of history that very much gave you and us all very fundamental and quintessential realities in our modernity like telling time, the idea of a calendar, of writing, of paper, the list goes on. I urge you all to come into conversation with this history and people, and to learn from this civilization, rather than voyeuristically observing and further fetishizing this very real and spectacular history. Perhaps I am biased because I am Egyptian, but I do think we can all learn from what we see around us in this space.

And quickly, the swarm turned towards me with questions not about Ancient Egypt––and I would not have been able to answer them if they were––but about me and modern Egypt. The most popular question was if Egypt was in Africa, and, after confirming that it was, if I considered myself African. Here, I struggled to provide an answer not because I did not have one but because I was unsure of how to navigate it: on the one hand, my identity is dimensional and far more abundant than the binaries present in North America between whiteness and blackness; it does not translate into the codified language of the United States of America when it comes to matters of race or identity. On the other hand, I, being Coptic Nubian Egyptian, wanted to proudly and loudly affirm my identity and enunciate it to a group of people that have probably never heard of my multiform identities. That is to say that we as Copts, as Nubians, exist too and make up the very fabric of our country. But, I simply confirmed that I do consider myself African because of the fact that I am Coptic Nubian Egyptian and explained Coptic as being Christian Orthodox and that our Coptic tongue comes from seven Hieroglyphic letters mixed with Ancient Greek.

I was also asked if the pyramids were in the middle of the desert and to that I replied that they were in fact not, that you could see them from your local Pizza Hut on the street in Giza. I was also asked if I rode camels to school and to that I replied that I do not go to school anymore and that I do not live in Egypt. By the time this last question came around, I denounced myself as spokesperson and representative of and for Egypt and Egyptians, because I felt as though I had said my piece already but also it had become exhausting and repetitive.

I left the MET angry and frustrated. Angry in the sense that I became too overwhelmed by the abundance of Ancient Egyptian artifacts on display. Angry in the sense that I wanted to breathe life into every single object and relic so that they come to a boil and tear the Crime Palace apart. Angry in the sense that I left being more frustrated not only in our representation and discourse in the West concerning our ancient history but also of our present realities.

In a rather short visit to the MET Museum that summer day, I remembered what it felt like to live in New York City and in the larger United States of America. There, I was reminded of my very real and big brown Egyptian non-American body in a North American space. I was reminded of the feeling of having to explain myself only to simply be and exist and the refusal of doing so because I wanted to simply be and exist. I was reminded again of my own body and identity and how it cannot and will not translate into this context, nor do I want it to. But then again, I am reminded that I have had to makeshift a translation everywhere I went and was met with bewilderment, or awe, with eagerness or sometimes intimidation and hesitation with a hint of fetishization. On that summer day, upon returning to New York City, I had decided that I will no longer reduce myself to better translate myself into this context, but rather, I will take from it and become, to exist and say that I am here too.

While I was metaphorically poked and prodded with questions and looked at with eyes of bewilderment like many of the Ancient Egyptian artifacts on display, I eventually willed myself to leave the Crime Palace. I wait for the day these artifacts’ souls return, when they grow legs and they too will themselves to leave a Crime Palace.

Egypt Migrations is always looking for people to contribute to our digital initiatives. Please contact team@egyptmigrations.com if you would like to join or support the organization.

Andrew Riad is a writing intern at Egypt Migrations. A Coptic Nubian Egyptian artist and poet, Riad is exploring the intersection of poetry, research and law. He works with textiles, text, filmography, photography, found objects, and culinary practices to undo a monolithic history and propose a [re]imagined and [re][un]written history revealing silenced narratives. Riad is a graduate of New York University Abu Dhabi (May, 2022) with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Literature and Creative Writing and Legal Studies and a current MFA (poetry) student at Pratt Institute (May, 2025).